Recent Articles & Podcasts

Some of the magazines I write for also post my articles on their on-line versions. Help yourself!

Vanishing Articles Reappear at Last

Colonial Williamsburg recently re-posted on its website the back issues of its national magazine, The Journal, and its more recent iteration, Trends & Traditions. Articles from twenty years ago are available to the general public once again, with accompanying illustrations and other features. Dozens of my own articles are among them. https://research.colonialwilliamsburg.org/foundation/journal/feature2.cfm?fbclid=IwAR0e558V2CB7ZjmebhbiO0Nib-dW8zCaCHCM_WcUClReYve-BYyC3qhPvT8

Colonial Williamsburg recently re-posted on its website the back issues of its national magazine, The Journal, and its more recent iteration, Trends & Traditions. Articles from twenty years ago are available to the general public once again, with accompanying illustrations and other features. Dozens of my own articles are among them. https://research.colonialwilliamsburg.org/foundation/journal/feature2.cfm?fbclid=IwAR0e558V2CB7ZjmebhbiO0Nib-dW8zCaCHCM_WcUClReYve-BYyC3qhPvT8

Brandermill Book Snags Local Publicity

A Richmond magazine devoted a long article with many photos to my Brandermill book.

Click here to see the online version. http://richmondmagazine.com/home/uncovering-brandermill/

DAR Headquarters Presentation: Women’s History Myths

In May I was invited to give a lecture at the DAR museum and headquarters in Washington, D.C., on history myths that pertain to women. The DAR records most of its visiting lecturers and posts the presentation online for those who couldn’t make it to the event. It’s about 35 minutes long. If you’d like to listen in, click on the word “lecture” above.

In May I was invited to give a lecture at the DAR museum and headquarters in Washington, D.C., on history myths that pertain to women. The DAR records most of its visiting lecturers and posts the presentation online for those who couldn’t make it to the event. It’s about 35 minutes long. If you’d like to listen in, click on the word “lecture” above.

Downton Abbey Exhibit: Virginia Historical Society lecture

I recently gave a talk at the Virginia Historical Society as part of their Downton Abbey exhibit, “Dressing Downton: Changing Fashions for Changing Times.” My talk was titled Weird-but-True Things Most People Don’t Know about the Roaring Twenties. It was a light, but serious, presentation which lasted 40 minutes (plus Q&A). In it, I shared some of the surprising things I learned during my research for my Roaring Twenties mystery series, things I have incorporated into my novels.

I recently gave a talk at the Virginia Historical Society as part of their Downton Abbey exhibit, “Dressing Downton: Changing Fashions for Changing Times.” My talk was titled Weird-but-True Things Most People Don’t Know about the Roaring Twenties. It was a light, but serious, presentation which lasted 40 minutes (plus Q&A). In it, I shared some of the surprising things I learned during my research for my Roaring Twenties mystery series, things I have incorporated into my novels.

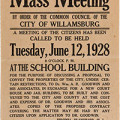

African-Americans during the Williamsburg Restoration

The leading local promoter of the restoration of Williams-burg to its eighteenth-century aspect, the Reverend Dr. W. A. R. Goodwin, summoned townspeople to a meeting June 12, 1928, to put his plan to a vote. A College of William and Mary fund-raiser and professor, as well as rector of Bruton Parish Church, he had negotiated the details with the city and county governments. They had surveyed public properties, drafted contracts, and secured the assent of Goodwin’s once-anonymous backer . . . The ballots tallied one hundred-fifty to four in favor, but not everyone with an interest in the outcome got to cast one, as pro forma as these may have been. In those years, seven hundred of the town’s 2,500 residents were African Americans. None attended the gathering. In Jim Crow’s Virginia, they could not enter the whites-only school. Williamsburg’s black citizens heard secondhand the official word that the town would become a museum, and that white Williamsburg had voted its approval. Click here for complete article.

The leading local promoter of the restoration of Williams-burg to its eighteenth-century aspect, the Reverend Dr. W. A. R. Goodwin, summoned townspeople to a meeting June 12, 1928, to put his plan to a vote. A College of William and Mary fund-raiser and professor, as well as rector of Bruton Parish Church, he had negotiated the details with the city and county governments. They had surveyed public properties, drafted contracts, and secured the assent of Goodwin’s once-anonymous backer . . . The ballots tallied one hundred-fifty to four in favor, but not everyone with an interest in the outcome got to cast one, as pro forma as these may have been. In those years, seven hundred of the town’s 2,500 residents were African Americans. None attended the gathering. In Jim Crow’s Virginia, they could not enter the whites-only school. Williamsburg’s black citizens heard secondhand the official word that the town would become a museum, and that white Williamsburg had voted its approval. Click here for complete article.

John Edwards, British Herbalist and Artist

There may be no better guide to the plants that grew in eighteenth-century gardens than The British Herbal, a rare collection of botanicals by artist John Edwards, published in 1770. “It’s one of the most valuable books we have,” said Wesley Greene, garden historian in Colonial Williamsburg’s historic trades department. “It lets us document the sort of plants that were available in the colonial era.” Edwards referenced Linnaeus for every plant, allowing Greene and others to identify species precisely. Click here for entire article.

There may be no better guide to the plants that grew in eighteenth-century gardens than The British Herbal, a rare collection of botanicals by artist John Edwards, published in 1770. “It’s one of the most valuable books we have,” said Wesley Greene, garden historian in Colonial Williamsburg’s historic trades department. “It lets us document the sort of plants that were available in the colonial era.” Edwards referenced Linnaeus for every plant, allowing Greene and others to identify species precisely. Click here for entire article.

More Murder She Wrote: the Poisoning of the Eminent George Wythe

Chancellor George Wythe ate strawberries and milk for supper May 24, 1806. The next morning, an hour after his usual light breakfast with coffee, he doubled up with stomach pain and vomiting. The following day and the day after, Wythe’s cook, the freedwoman Lydia Broadnax, and the freed lad Michael Brown fell violently ill. Within days, suspicion fell on the fourth member of the household, teenager George Wythe Swinney. Click here to read entire article.

Chancellor George Wythe ate strawberries and milk for supper May 24, 1806. The next morning, an hour after his usual light breakfast with coffee, he doubled up with stomach pain and vomiting. The following day and the day after, Wythe’s cook, the freedwoman Lydia Broadnax, and the freed lad Michael Brown fell violently ill. Within days, suspicion fell on the fourth member of the household, teenager George Wythe Swinney. Click here to read entire article.

Hot off the Press!

“Thomas Jefferson and the Maple Sugar Scheme”

Thomas Jefferson came late to the maple sugar scheme. He was an ocean away in Paris, serving as the United States’ minister to France, when a group of Quakers and Dr. Benjamin Rush collaborated in Philadelphia to promote maple sugar over cane sugar. The advantages of maple sugar were many, Rush wrote, but the clincher was its moral superiority: Cane sugar was grown by slaves, maple sugar by free Americans. His goal was “to lessen or destroy the consumption of West Indian sugar, and thus indirectly to destroy negro slavery.”

Thomas Jefferson came late to the maple sugar scheme. He was an ocean away in Paris, serving as the United States’ minister to France, when a group of Quakers and Dr. Benjamin Rush collaborated in Philadelphia to promote maple sugar over cane sugar. The advantages of maple sugar were many, Rush wrote, but the clincher was its moral superiority: Cane sugar was grown by slaves, maple sugar by free Americans. His goal was “to lessen or destroy the consumption of West Indian sugar, and thus indirectly to destroy negro slavery.”

More Magazine Articles

“How the West Was Lost”

Pity West Virginia schoolchildren, having to study two state histories! They must first learn about Virginia’s origins in 1607 and then, when the teacher reaches the Civil War, begin anew with the birth of their own breakaway state. Not only that, but they must also try to make sense of what is surely the most complicated creation story of all the states in America, layered as it is with dubious elections, conventions and referendums, questionable legalities, parallel governments, appalling wartime violence and enough political factions to make the Balkans look harmonious. (Keep reading . . .)

The cochineal is an odd sort of bug. The female lives her life in a spot on a nopal cactus, or prickly pear. As soon as she hatches, she buries her mouth in the cactus pad and starts sucking. She will live, breed, and die on that spot, parasitically attached to the cactus beneath a bit of cottony fluff. The males have wings and lead more exciting lives, flying about in search of females. But the price for their mobility is a one-week lifespan—their mouthparts deteriorate, and they starve. The female, not much bigger than the head of a pin, lays her eggs on the cactus and continues to feed. Her offspring, if they are not blown by the wind to another nopal, crawl only as far as they must to find a place to dig in, and the cycle repeats. (Keep reading . . .)

The cochineal is an odd sort of bug. The female lives her life in a spot on a nopal cactus, or prickly pear. As soon as she hatches, she buries her mouth in the cactus pad and starts sucking. She will live, breed, and die on that spot, parasitically attached to the cactus beneath a bit of cottony fluff. The males have wings and lead more exciting lives, flying about in search of females. But the price for their mobility is a one-week lifespan—their mouthparts deteriorate, and they starve. The female, not much bigger than the head of a pin, lays her eggs on the cactus and continues to feed. Her offspring, if they are not blown by the wind to another nopal, crawl only as far as they must to find a place to dig in, and the cycle repeats. (Keep reading . . .)

Conquistador Girolamo Benzoni, one of the first to taste the spicy Aztec beverage called cacahuatl, wrote, “It seemed more a drink for pigs than a drink for humanity. I was in this country for more than a year and never wanted to taste it, and whenever I passed a settlement, some Indian would offer me a drink of it and would be amazed when I would not accept, going away laughing. But then, as there was a shortage of wine. . . .” Keep reading . . .

Conquistador Girolamo Benzoni, one of the first to taste the spicy Aztec beverage called cacahuatl, wrote, “It seemed more a drink for pigs than a drink for humanity. I was in this country for more than a year and never wanted to taste it, and whenever I passed a settlement, some Indian would offer me a drink of it and would be amazed when I would not accept, going away laughing. But then, as there was a shortage of wine. . . .” Keep reading . . .

Lie #1: Most colonial Americans were illiterate, so shop signs had to have pictures on them. Shop signs and inn signs with pictures were no doubt helpful to people who couldn’t read, but mass illiteracy does not account for their use. Keep reading . . .

Lie #1: Most colonial Americans were illiterate, so shop signs had to have pictures on them. Shop signs and inn signs with pictures were no doubt helpful to people who couldn’t read, but mass illiteracy does not account for their use. Keep reading . . .

There are more myths about the origins of ice cream than flavors at Baskin-Robbins. Debunking them is among the jobs of the Historic Trades cooks at Colonial Williamsburg’s Governor’s Palace kitchens. They concoct eighteenth-century versions of the frozen treat in front of guests every month.

There are more myths about the origins of ice cream than flavors at Baskin-Robbins. Debunking them is among the jobs of the Historic Trades cooks at Colonial Williamsburg’s Governor’s Palace kitchens. They concoct eighteenth-century versions of the frozen treat in front of guests every month.

Some sources say the ancient Romans invented ice cream, others that Marco Polo brought the discovery back to Italy from China. All agree that Catherine de Medici introduced the French to ice cream when she married the future King Henri II. Not to be outdone by Europeans, some Americans have said ice cream was first made by Martha Washington, or brought to this country from France by Thomas Jefferson, or invented by First Lady Dolley Madison at the White House. By dint of repetition, these entertaining tall tales go unchallenged—at least until they reach the Governor’s Palace kitchen. Read more . . .

“Some Pumpkins! Halloween and Pumpkins in Colonial America”

Colonial Americans didn’t celebrate Halloween. They didn’t have jack-o’-lanterns either, or trick or treat, or costumes, or candy as we know it. What they had were pumpkins— large and small, round and oval, warty and smooth, squat and misshapen, orange, yellow, and green, far more varieties of the fruit than we see today, all of which they consumed in far greater quantities than we do today. As America once again decorates its porches with grimacing pumpkins and braces for the annual onslaught of princesses and caped crusaders, one can’t help wondering what our forebears would have thought of these Halloween rituals. It seems likely that Indians and colonists alike would have been puzzled by the candlelit faces, aghast at the waste of good food, and appalled when they saw the smashed remains littering the streets.

Colonial Americans didn’t celebrate Halloween. They didn’t have jack-o’-lanterns either, or trick or treat, or costumes, or candy as we know it. What they had were pumpkins— large and small, round and oval, warty and smooth, squat and misshapen, orange, yellow, and green, far more varieties of the fruit than we see today, all of which they consumed in far greater quantities than we do today. As America once again decorates its porches with grimacing pumpkins and braces for the annual onslaught of princesses and caped crusaders, one can’t help wondering what our forebears would have thought of these Halloween rituals. It seems likely that Indians and colonists alike would have been puzzled by the candlelit faces, aghast at the waste of good food, and appalled when they saw the smashed remains littering the streets.

“When Whiskey Was the King of Drink“

Virginia farmer Chuck Miller gave up wine for whiskey twenty-two years ago. “Growing grapes just didn’t work,” he says. “One day I came across my grandfather’s old recipe for moonshine and decided to try to make that—legally this time.” He got a license, bought a 1935 bottling machine and an antique pot still, and started distilling corn whiskey on his Culpeper spread. Miller says he’s following in his grandfather’s Prohibition-era footsteps, but whiskey making in Virginia goes back farther than that. It began about 1620, when colonist George Thorpe figured out he could distill a mash of Indian corn. “Wee have found a waie to make soe good drink of Indian corne I have divers times refused to drinke good stronge English beare and chose to drinke that,” he wrote to his cousin in England, John Smith of Nibley. (To continue reading, click here.)

Virginia farmer Chuck Miller gave up wine for whiskey twenty-two years ago. “Growing grapes just didn’t work,” he says. “One day I came across my grandfather’s old recipe for moonshine and decided to try to make that—legally this time.” He got a license, bought a 1935 bottling machine and an antique pot still, and started distilling corn whiskey on his Culpeper spread. Miller says he’s following in his grandfather’s Prohibition-era footsteps, but whiskey making in Virginia goes back farther than that. It began about 1620, when colonist George Thorpe figured out he could distill a mash of Indian corn. “Wee have found a waie to make soe good drink of Indian corne I have divers times refused to drinke good stronge English beare and chose to drinke that,” he wrote to his cousin in England, John Smith of Nibley. (To continue reading, click here.)

“Stuff and Nonsense: Myths That Should by Now Be History”

Every day, stories about people or objects are told in museums that are not true. Some are outright fabrications. Others contain a kernel of truth that the years have embellished. Still others could be true, but lack the proof of documentation. Because they are catchy, humorous, or shocking, the stories stick in our memories when information less sexy slips away. (To continue reading, click here.)

Every day, stories about people or objects are told in museums that are not true. Some are outright fabrications. Others contain a kernel of truth that the years have embellished. Still others could be true, but lack the proof of documentation. Because they are catchy, humorous, or shocking, the stories stick in our memories when information less sexy slips away. (To continue reading, click here.)

Sometime after the Pilgrims landed in Massachusetts, they learned from the Pequot Indians of an edible berry called ibimi, or “bitter berry.” The Indians mixed these berries with dried venison and fat to make pemmican, a long-lasting, portable fast food for hunting trips or trade expeditions. Ibimi berries are red, and the juice worked nicely as a red dye. They served, too, for a poultice for healing wounds because, raw, they have an astringent effect that reduces bleeding. The story goes that the Pilgrims, who had never seen such a fruit, were struck by the ibimi flower’s resemblance to the head and bill of a sandhill crane and so named them crane-berries. This, however, sounds suspiciously like one of those Parson Weems fables about chopping down cherry trees—charming but fictional. Keep reading . . .

Sometime after the Pilgrims landed in Massachusetts, they learned from the Pequot Indians of an edible berry called ibimi, or “bitter berry.” The Indians mixed these berries with dried venison and fat to make pemmican, a long-lasting, portable fast food for hunting trips or trade expeditions. Ibimi berries are red, and the juice worked nicely as a red dye. They served, too, for a poultice for healing wounds because, raw, they have an astringent effect that reduces bleeding. The story goes that the Pilgrims, who had never seen such a fruit, were struck by the ibimi flower’s resemblance to the head and bill of a sandhill crane and so named them crane-berries. This, however, sounds suspiciously like one of those Parson Weems fables about chopping down cherry trees—charming but fictional. Keep reading . . .

“A Monstrous Absurdity: the Gunpowder Theft”

A Scot named Miller first leaked the word. The armorer hired to clean and repair the public arms, he was the first to know. Lord Dunmore, governor of Virginia, had ordered the gunlocks taken off most of the firearms in Williamsburg’s Magazine and was planning to seize its stores of gunpowder. The city, the capital of the colony, treated the rumor seriously—for about a week. Citizens patrolled the streets and guarded the Magazine at night. But, according to a historian writing thirty years after the event, “at length disbelieving it, they grew a little negligent and on Thursday night the 20th” of April, 1775, “discharged their guards.” (Continue reading, click here)

A Scot named Miller first leaked the word. The armorer hired to clean and repair the public arms, he was the first to know. Lord Dunmore, governor of Virginia, had ordered the gunlocks taken off most of the firearms in Williamsburg’s Magazine and was planning to seize its stores of gunpowder. The city, the capital of the colony, treated the rumor seriously—for about a week. Citizens patrolled the streets and guarded the Magazine at night. But, according to a historian writing thirty years after the event, “at length disbelieving it, they grew a little negligent and on Thursday night the 20th” of April, 1775, “discharged their guards.” (Continue reading, click here)

“Slave Conspiracies in Colonial Virginia”

There was in colonial Virginia a relentless fear of slave uprisings. Rumors and reports fed the anxieties of a slaveholding society, and some of them were founded in fact. But there was no organized slave uprising in Virginia until well into the nineteenth century. All the plots were uncovered or betrayed before they could be carried out. Luck—bad for the slaves, good for the masters—played a role, but there were other factors. One was the number of slaves in the colony and the ability of those slaves to communicate with one another. Until the early years of the eighteenth century, there were too few slaves in Virginia to form a critical mass. Illiteracy and the lack of a common language among transported Africans scattered across unfamiliar territory hindered communication. So did distances between plantations. As conditions changed, Virginia slave conspiracies became more frequent. But not until the antebellum period did one become an insurrection. (Continue reading, click here)

There was in colonial Virginia a relentless fear of slave uprisings. Rumors and reports fed the anxieties of a slaveholding society, and some of them were founded in fact. But there was no organized slave uprising in Virginia until well into the nineteenth century. All the plots were uncovered or betrayed before they could be carried out. Luck—bad for the slaves, good for the masters—played a role, but there were other factors. One was the number of slaves in the colony and the ability of those slaves to communicate with one another. Until the early years of the eighteenth century, there were too few slaves in Virginia to form a critical mass. Illiteracy and the lack of a common language among transported Africans scattered across unfamiliar territory hindered communication. So did distances between plantations. As conditions changed, Virginia slave conspiracies became more frequent. But not until the antebellum period did one become an insurrection. (Continue reading, click here)

A colonial Christmas celebration focused on food. For Virginia’s landed gentry, that meant a lavish presentation of meats, game, fowl, and preserved fruits and vegetables crowding the dining table alongside preparations of fish and seafood taken from Tidewater rivers and the Chesapeake Bay. There were baked goods too, large cakes and small cakes—called cookies today—and a variety of sweetmeats, a term that encompassed jellies, candied fruits and nuts, marzipan, and other sugary delicacies. The main meal was served in the mid afternoon on an elaborately arranged table dressed with a fine white linen or damask cloth. At an important dinner like Christmas, two courses of desserts would usually follow two courses of meat and vegetables, the main visual difference being the absence of a table cloth for the dessert couses. Between courses, guests retired to another room while servants or slaves cleared the table and set it again. At a Chrismas ball, guest would be treated to an evening “dessert table,” a feast for the eyes as well as the palate. Obsessed with symmetry in architecture, garden, and decorative arts, colonial Virginians were no less mindful of their tabletop design—each dish of food was precisely balanced with a similarly sized dish on the opposite side of the table. (Continue reading, click here)

A colonial Christmas celebration focused on food. For Virginia’s landed gentry, that meant a lavish presentation of meats, game, fowl, and preserved fruits and vegetables crowding the dining table alongside preparations of fish and seafood taken from Tidewater rivers and the Chesapeake Bay. There were baked goods too, large cakes and small cakes—called cookies today—and a variety of sweetmeats, a term that encompassed jellies, candied fruits and nuts, marzipan, and other sugary delicacies. The main meal was served in the mid afternoon on an elaborately arranged table dressed with a fine white linen or damask cloth. At an important dinner like Christmas, two courses of desserts would usually follow two courses of meat and vegetables, the main visual difference being the absence of a table cloth for the dessert couses. Between courses, guests retired to another room while servants or slaves cleared the table and set it again. At a Chrismas ball, guest would be treated to an evening “dessert table,” a feast for the eyes as well as the palate. Obsessed with symmetry in architecture, garden, and decorative arts, colonial Virginians were no less mindful of their tabletop design—each dish of food was precisely balanced with a similarly sized dish on the opposite side of the table. (Continue reading, click here)

The morning of March 22, 1622, Virginia’s Powhatan Indian alliance executed a well-conceived and coordinated attack on English settlements spread more than fifty miles up and down the James River. Warriors from perhaps a dozen of the thirty-two affiliated tribes—Quiyoughcohannocks, Waraskoyacks, Weanocks, Appomatucks, Arrohatecks, and others—fell on men, women, and children in their homes and in their fields, burning houses and barns, killing livestock, mutilating the bodies of their victims. Planned by the Pamunkey headman Opechancanough, kinsman of the now-deceased paramount chieftain Powhatan, the offensive slew about 350 whites, a sixth of the total in the fifteen-year-old colony. From modern Richmond to Hampton Roads, the onslaught devastated Jamestown’s outlying plantations, but it failed of its purpose: stopping the relentless encroachment of the English. Settlers kept coming, expropriating native lands, killing Indians who got in the way, and twenty-two years later, Opechancanough organized a second attempt. Five hundred English died this time, but by 1644 there were so many colonists that the impact was not as severe, and a wave of retaliation reduced the Indian threat in Tidewater almost to a memory. A question lingered, however, one yet to be answered to everyone’s satisfaction: How had Opechancanough synchronized the strikes of widely dispersed tribes against scattered targets across so many square miles? (Continue reading, click here)

The morning of March 22, 1622, Virginia’s Powhatan Indian alliance executed a well-conceived and coordinated attack on English settlements spread more than fifty miles up and down the James River. Warriors from perhaps a dozen of the thirty-two affiliated tribes—Quiyoughcohannocks, Waraskoyacks, Weanocks, Appomatucks, Arrohatecks, and others—fell on men, women, and children in their homes and in their fields, burning houses and barns, killing livestock, mutilating the bodies of their victims. Planned by the Pamunkey headman Opechancanough, kinsman of the now-deceased paramount chieftain Powhatan, the offensive slew about 350 whites, a sixth of the total in the fifteen-year-old colony. From modern Richmond to Hampton Roads, the onslaught devastated Jamestown’s outlying plantations, but it failed of its purpose: stopping the relentless encroachment of the English. Settlers kept coming, expropriating native lands, killing Indians who got in the way, and twenty-two years later, Opechancanough organized a second attempt. Five hundred English died this time, but by 1644 there were so many colonists that the impact was not as severe, and a wave of retaliation reduced the Indian threat in Tidewater almost to a memory. A question lingered, however, one yet to be answered to everyone’s satisfaction: How had Opechancanough synchronized the strikes of widely dispersed tribes against scattered targets across so many square miles? (Continue reading, click here)

“Henricus: A New and Improved Jamestown”

The Virginia Company of London’s Sir Thomas Dale shipped up the James River in the summer of 1611 searching for a place to plant a new and improved version of Jamestown—the flagging first permanent English settlement in America thirty miles downstream. It would be called the Citie of Henrico or Henricus in honor of Prince Henry, heir to the English throne and a great supporter of the Virginia colony. The town would have a shorter life than its namesake—a dozen years to the prince’s eighteen—but its significance was greater than that suggests. While Dale scouted for a suitable site, laborers in Jamestown were ordered to start cutting “pales, posts and railes to impaile his proposed new Towne.” Instructions to Dale and to Governor Thomas Gates from the Virginia Company, which owned and financed the Virginia enterprise, made clear that Henricus would become the colony’s new seat, and so required a location that was healthier and easier to defend than Jamestown. (Continue reading, click here)

The Virginia Company of London’s Sir Thomas Dale shipped up the James River in the summer of 1611 searching for a place to plant a new and improved version of Jamestown—the flagging first permanent English settlement in America thirty miles downstream. It would be called the Citie of Henrico or Henricus in honor of Prince Henry, heir to the English throne and a great supporter of the Virginia colony. The town would have a shorter life than its namesake—a dozen years to the prince’s eighteen—but its significance was greater than that suggests. While Dale scouted for a suitable site, laborers in Jamestown were ordered to start cutting “pales, posts and railes to impaile his proposed new Towne.” Instructions to Dale and to Governor Thomas Gates from the Virginia Company, which owned and financed the Virginia enterprise, made clear that Henricus would become the colony’s new seat, and so required a location that was healthier and easier to defend than Jamestown. (Continue reading, click here)

“The Community Christmas Tree”

A small notice in the town newspaper spread the word: “When the bells begin to ring all of Williamsburg will assemble on Palace Green to sing carols and hear the exercises that have been prepared for the community Christmas tree.” On Christmas night, 1915, townspeople gathered around a tall evergreen decorated with electric lights. They offered prayers, sang carols, delivered recitations, and joined in a chorus of happy exclamation as they lit their first community Christmas tree. The idea came from Madison Square Garden in New York City, where America’s first community Christmas tree had been erected three years earlier. A towering pine, the focal point of an outdoor celebration that embraced the city’s diverse ethnic heritage, was hoisted into place and covered with a galaxy of twinkling electric lights. (Keep reading)

A small notice in the town newspaper spread the word: “When the bells begin to ring all of Williamsburg will assemble on Palace Green to sing carols and hear the exercises that have been prepared for the community Christmas tree.” On Christmas night, 1915, townspeople gathered around a tall evergreen decorated with electric lights. They offered prayers, sang carols, delivered recitations, and joined in a chorus of happy exclamation as they lit their first community Christmas tree. The idea came from Madison Square Garden in New York City, where America’s first community Christmas tree had been erected three years earlier. A towering pine, the focal point of an outdoor celebration that embraced the city’s diverse ethnic heritage, was hoisted into place and covered with a galaxy of twinkling electric lights. (Keep reading)

She was the daughter of one earl and the wife of another; she marched in George III’s coronation procession; she paid morning visits to the queen. And she left her life of luxury in the dead of winter 1773 to brave the treacherous Atlantic with her children and join her husband in Williamsburg. Lady Charlotte Murray, wife of Virginia’s governor, John Murray, the fourth Earl of Dunmore, had planned to winter in Naples. But Lord Dunmore wanted his family with him, and, as he could not visit them in England without resigning, they must come to him. He sent his personal secretary to deliver the message and accompany them on the voyage. (Click here to keep reading)

She was the daughter of one earl and the wife of another; she marched in George III’s coronation procession; she paid morning visits to the queen. And she left her life of luxury in the dead of winter 1773 to brave the treacherous Atlantic with her children and join her husband in Williamsburg. Lady Charlotte Murray, wife of Virginia’s governor, John Murray, the fourth Earl of Dunmore, had planned to winter in Naples. But Lord Dunmore wanted his family with him, and, as he could not visit them in England without resigning, they must come to him. He sent his personal secretary to deliver the message and accompany them on the voyage. (Click here to keep reading)

“A New Look at Old Wetherburn’s”

“A New Look at Old Wetherburn’s”

Tavernkeeper Henry Wetherburn catered to Virginia’s elite. His establishment on Williamsburg’s Duke of Gloucester Street provided lodging, food, and entertainment that met the expectations of the most discriminating colonial clientele. With fashionable furniture, fine linens, Chinese porcelain dinnerware, sterling candlesticks, good food, and a cellar full of imported alcohol, Wetherburn offered the comforts of home to his well-heeled guests—and there were as well more modest accommodations for the middling sort. Two hundred and fifty years later, his tavern is still a thriving place of business. But it is the history business that brings in the travelers today. The chance to peer back through time into the busy lives of a prosperous innkeeper and his family, slaves, and guests draws scores of curious visitors every day. The building’s recent refurbishing brings a new perspective to an important eighteenth-century original and a better understanding of the people who interacted there. (Click here to keep reading)

The 1901 marriage of the son of the richest man in America to the daughter of the most powerful man in the United States Senate had every outward appearance of a corporate merger. Acquaintances of the bride and groom knew better, although many of them—including the couple’s siblings—wondered how such different personalities would fare in the bonds of holy matrimony. John D. Rockefeller Jr. was not the Gay Nineties model of a rich man’s son. Raised in a strict Baptist household to shun dancing, drinking, and parties, Rockefeller was a shy, cautious young man. Frivolity and extravagance were alien. As he said, he was the sort who got lost in a crowd, and he did not make friends easily. Self-conscious about his name, he was at a loss when it came to courting. While he was a Brown University undergraduate in Providence, Rhode Island, he met Abby Greene Aldrich at the first college dance he attended. Six years passed before he could bring himself to propose, but it seemed as if they found in each other’s personalities the reciprocals of their own. (click here to keep reading)

The 1901 marriage of the son of the richest man in America to the daughter of the most powerful man in the United States Senate had every outward appearance of a corporate merger. Acquaintances of the bride and groom knew better, although many of them—including the couple’s siblings—wondered how such different personalities would fare in the bonds of holy matrimony. John D. Rockefeller Jr. was not the Gay Nineties model of a rich man’s son. Raised in a strict Baptist household to shun dancing, drinking, and parties, Rockefeller was a shy, cautious young man. Frivolity and extravagance were alien. As he said, he was the sort who got lost in a crowd, and he did not make friends easily. Self-conscious about his name, he was at a loss when it came to courting. While he was a Brown University undergraduate in Providence, Rhode Island, he met Abby Greene Aldrich at the first college dance he attended. Six years passed before he could bring himself to propose, but it seemed as if they found in each other’s personalities the reciprocals of their own. (click here to keep reading)

“The Colonial Revival: The Past that Never Dies”

Preservation feaver swept America in the 1920s. Virginia, with more colonial buildings than most states, was hard hit. Private individuals and preservation societies snapped up derelict plantation homes and restored and furnished them for personal use or to open to the public. In Virginia, Monticello, Stratford Hall, Montpelier, Oak Hill, Brandon, Kenmore, Ampthill, Carter’s Grove, and dozens more were saved from ruin. Creating museums from historic buildings became a preferred philanthropy for the wealthy: in Michigan, Henry Ford started Greenfield Village; in Delaware, the DuPonts began transforming Winterthur inside and out. And John D. Rockefeller Jr. launched the largest single preservation project the country had seen: Colonial Williamsburg. Symptoms of the preservation epidemic had begun to appear as early as the 1840s. “Fashion has taken up antiquity,” wrote a member of the American Antiquarian Society in 1842. “Old pictures, old furniture, old plate and even old books which have heretofore suffered neglect . . . are now sought with eagerness as necessary adjuncts of style.” New York’s Metropolitan Museum, which had validated the collecting impulse in 1909 with the first exhibit devoted to American furniture, opened in 1924 an American Wing with period rooms full of American antiques. By the Roaring Twenties, collecting had transcended objects. For those who could afford it, an antique house—restored, modernized, and appropriately furnished—became the ultimate fashion statement. (Click here to keep reading)

Preservation feaver swept America in the 1920s. Virginia, with more colonial buildings than most states, was hard hit. Private individuals and preservation societies snapped up derelict plantation homes and restored and furnished them for personal use or to open to the public. In Virginia, Monticello, Stratford Hall, Montpelier, Oak Hill, Brandon, Kenmore, Ampthill, Carter’s Grove, and dozens more were saved from ruin. Creating museums from historic buildings became a preferred philanthropy for the wealthy: in Michigan, Henry Ford started Greenfield Village; in Delaware, the DuPonts began transforming Winterthur inside and out. And John D. Rockefeller Jr. launched the largest single preservation project the country had seen: Colonial Williamsburg. Symptoms of the preservation epidemic had begun to appear as early as the 1840s. “Fashion has taken up antiquity,” wrote a member of the American Antiquarian Society in 1842. “Old pictures, old furniture, old plate and even old books which have heretofore suffered neglect . . . are now sought with eagerness as necessary adjuncts of style.” New York’s Metropolitan Museum, which had validated the collecting impulse in 1909 with the first exhibit devoted to American furniture, opened in 1924 an American Wing with period rooms full of American antiques. By the Roaring Twenties, collecting had transcended objects. For those who could afford it, an antique house—restored, modernized, and appropriately furnished—became the ultimate fashion statement. (Click here to keep reading)

“Christmas Williamsburg Style“

When it came to excessive eating and drinking during the Christmas season, Englishmen and colonial Virginians had much in common. A sumptously spread Christmas table had long been a mark of status in Great Britain and it was no less true across the sea. Colonial gentry, like their English counterparts, imitated the aristocractic penchant for dining tables crowded with food. Conspicuous consumption was at its height. In the 18th century, Christmas offered unlimited opportunities for feasting. Then as now, people gathered with family and friends to celebrate the holidays with the very best they had to offer. Because the season always brought a flurry of weddings, there were wedding feasts to enjoy in addition to lavish midday dinners on Christmas and New Year’s Day. In some Southern homes, Twelfth Night, January 6, was the more festive occasion. “It seems,” wrote an Englishman traveling through Virginia shortly before the Revolution, “this is one of their annual Balls supported in the following manner: A large rich cake is provided and cut into small pieces and handed round to the company, who at the same time draws a ticket out of a Hat with something merry wrote on it. He that draws the King has the Honor of treating the company with a Ball the next year…The Lady that draws the Queen has the trouble of making the Cake.” (Click here to keep reading)

When it came to excessive eating and drinking during the Christmas season, Englishmen and colonial Virginians had much in common. A sumptously spread Christmas table had long been a mark of status in Great Britain and it was no less true across the sea. Colonial gentry, like their English counterparts, imitated the aristocractic penchant for dining tables crowded with food. Conspicuous consumption was at its height. In the 18th century, Christmas offered unlimited opportunities for feasting. Then as now, people gathered with family and friends to celebrate the holidays with the very best they had to offer. Because the season always brought a flurry of weddings, there were wedding feasts to enjoy in addition to lavish midday dinners on Christmas and New Year’s Day. In some Southern homes, Twelfth Night, January 6, was the more festive occasion. “It seems,” wrote an Englishman traveling through Virginia shortly before the Revolution, “this is one of their annual Balls supported in the following manner: A large rich cake is provided and cut into small pieces and handed round to the company, who at the same time draws a ticket out of a Hat with something merry wrote on it. He that draws the King has the Honor of treating the company with a Ball the next year…The Lady that draws the Queen has the trouble of making the Cake.” (Click here to keep reading)

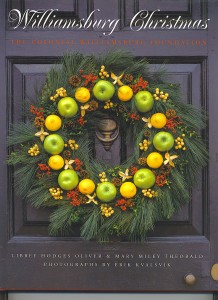

They didn’t originate in Williamsburg–those fruit bedecked wreaths and swags that decorate America’s front doors–nor did they begin during colonial times. No matter. Everyone from Augusta to Albuquerque calls them “Colonial Williamsburg door decorations” anyway and millions of people have visited the Historic Area during the Christmas season for the sole purpose of admiring them. The custom of affixing fruits, vegetables, dried flowers, herbs, and other plant life to basic Christmas forms like wreaths, swags, and roping traces its roots to the early years of the twentieth century, a time when Christmas was growing in significance and the Colonial Revival was pulling decorative impulses back toward the eighteenth century. A 1926 issue of House Beautiful illustrates several fruit-laden wreaths and explains, “Of late years, besides the staple wreaths of plain greens to which we have long been accustomed, the holiday’s emblems have blossomed forth,–or perhaps we should say fruited forth,–with richness of color produced by the use of either natural or artificial fruit as an embellishment. This idea was undoubtedly suggested by the gorgeous Italian carvings and terra cottas of the Renaissance. . .” (Click here to keep reading)

They didn’t originate in Williamsburg–those fruit bedecked wreaths and swags that decorate America’s front doors–nor did they begin during colonial times. No matter. Everyone from Augusta to Albuquerque calls them “Colonial Williamsburg door decorations” anyway and millions of people have visited the Historic Area during the Christmas season for the sole purpose of admiring them. The custom of affixing fruits, vegetables, dried flowers, herbs, and other plant life to basic Christmas forms like wreaths, swags, and roping traces its roots to the early years of the twentieth century, a time when Christmas was growing in significance and the Colonial Revival was pulling decorative impulses back toward the eighteenth century. A 1926 issue of House Beautiful illustrates several fruit-laden wreaths and explains, “Of late years, besides the staple wreaths of plain greens to which we have long been accustomed, the holiday’s emblems have blossomed forth,–or perhaps we should say fruited forth,–with richness of color produced by the use of either natural or artificial fruit as an embellishment. This idea was undoubtedly suggested by the gorgeous Italian carvings and terra cottas of the Renaissance. . .” (Click here to keep reading)

“Dressing for the

Murder Off Stage

Murder Off Stage

like me on Facebook follow me on twitter linkedin pinterest rss