Silent Murders

Follow The Roaring Twenties mysteries on Facebook for the latest details.

In the second Roaring Twenties murder mystery, Jessie trades her nomadic vaudeville life for a modest but steady job in the silent film industry. She quickly learns that all Hollywood scorns the Prohibition laws: studio bosses rule the police and gangsters supply speakeasies everywhere with bootleg hooch and Mexican dope. When a powerful director is murdered at his own party and Jessie’s waitress friend is killed for what she saw, Jessie takes the lead in an investigation tainted by corrupt cops. Soon tangled in a web of drugs, bribery, and greed, she finds herself a prime suspect as the bodies pile up.

In the second Roaring Twenties murder mystery, Jessie trades her nomadic vaudeville life for a modest but steady job in the silent film industry. She quickly learns that all Hollywood scorns the Prohibition laws: studio bosses rule the police and gangsters supply speakeasies everywhere with bootleg hooch and Mexican dope. When a powerful director is murdered at his own party and Jessie’s waitress friend is killed for what she saw, Jessie takes the lead in an investigation tainted by corrupt cops. Soon tangled in a web of drugs, bribery, and greed, she finds herself a prime suspect as the bodies pile up.

I don’t think an Oscar is headed my way, but I did my best in this interview on “Virginia This Morning.”

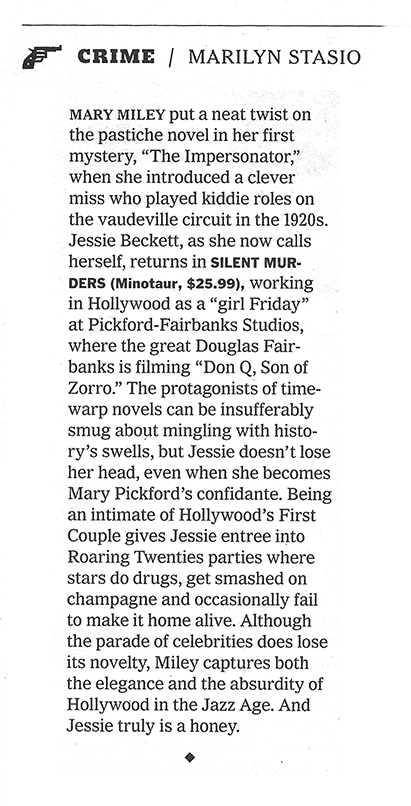

New York Times review (Oct. 19, 2014)

Publisher’s Weekly review (July 21, 2014)

Miley draws on the unsolved 1922 murder of Hollywood director William Desmond Taylor for her absorbing followup to THE IMPERSONATOR (2013). In 1925, former vaudevillian Jessie Beckett is working as a script girl when she received a dream assignment: temporary assistant to swashbuckling legend Douglas Fairbanks. To her delight, director Bruno Heilmann invites her to a party at his home, where she has a chance encounter with an old family friend. Alas, the friend and Heilmann turn up dead, and two partygoers are poisoned. The authorities sniff suspiciously around Jessie and the shady David Carr after they discover drugs at Heilmann’s house. Jessie and a sharp cop suspect that more lies behind the murders, and Fairbanks is worried about the potential involvement of his alcoholic sister-in-law. Readers will enjoy the novel’s taut climax, cameos by famous and future stars, and a resourceful heroine who uses her acting skills in investigating and escaping from trouble.

Kirkus review (Aug. 26, 2014)

What happens off camera is as dramatic as what’s in the frame when serial murders intrude on Jazz Age Hollywood. Now that her recent masquerade as heiress (The Impersonator, 2013) has come to a disastrous end, vaudeville veteran Leah Randall is ready to adopt a new identity as Jessie Beckett, script girl in training and personal assistant to Douglas Fairbanks at the silent-film studio he and his wife, Mary Pickford, own and run. Jessie’s tasks are limited to checking script continuity and running errands until a dinner party at the home of director Bruno Heilmann ends in the host’s murder. Then her job description expands to include beating the police to the deceased’s house so she can collect any evidence Mary’s unstable sister, Lottie, left behind. Lottie had a secret affair with Bruno, and Fairbanks and Pickford dread the scandal that might result from the discovery. A more personal loss for Jessie is Esther Frankel, an unwilling witness who’d shared a stage with Jessie’s late mother. But when Jessie comes for tea and the souvenirs Esther promised, she finds the older woman dead from a blow to the head. Working with a conscientious detective and a charming bootlegger she knew from her days of passing for an heiress, Jessie tries to figure out whether and how the two murders are related to two other Hollywood deaths. Accompanied by fresh-faced professional dancer Myrna Williams, who’s trying on a new surname while she attempts to launch a Hollywood career, Jessie follows the trail of her chief suspect through an underworld connection and corruption that may reach high into the local hierarchy to a denouement featuring perhaps one Hollywood icon too many. A brisk, knowing adventure whose self-reliant but vulnerable heroine takes big risks for her Hollywood boss and stops just short of romance with two men who couldn’t be more different. Only the sequel will tell which one she chooses and who she’ll be next.

Sample: First Two Chapters

Chapter 1

Turns out vaudeville doesn’t prepare you for Hollywood.

I’m a quick study and good at figuring things out, but it was a week before I could navigate the eighteen acres of stages, sets, and storage rooms at Pickford-Fairbanks Studios. It was another week before I got straight in my head the pecking order of all the directors, general managers, collaborators, producers, and other big shots and learned to tell the actors from the extras and the gaffers from the grips. To be safe, I called everyone Mister or Miss until they said otherwise.

Everyone called me Jessie. And everyone called me a lot. Officially I was Assistant Script Girl to director Frank Richardson on the Don Q: Son of Zorro set, but anyone in the studio could waylay me at any time. I felt like a lowly worker bee, flitting in and out of the beehive on foraging expeditions.

“Jessie, run to Wardrobe and get Paul Burns—the Queen has ripped her ball gown.”

“There you are, Jessie. We need wind. Find two electric fans, pronto.”

“Oh, Jessie? More ice water for Mr. Fairbanks before he films that stunt again.”

“Quick, Jessie, the shovel! Somebody oughta quit feeding those damned horses.”

But I was lucky to have the job, and I loved being part of the excitement of creating moving pictures. Pickford-Fairbanks Studios made even Big Time vaudeville seem Small Time.

The film industry had started moving to the Los Angeles area a dozen years ago, drawn by sunshine, scenery, and cheap labor. I was part of that last feature. Locals called us moving picture people “movies” and avoided us when they could, but the number of “movies” grew with every passing day while locals seemed to evaporate into the warm, dry air. By my count, there were seventeen studios in town and Pickford-Fairbanks was not among the largest. But it was the only one started by actors: Mary Pickford and her husband Douglas Fairbanks, the queen and king of Hollywood.

I’d been on the job two weeks when America’s most famous leading man first took notice of me. We were in the early days of filming Don Q: Son of Zorro, shooting one of the final scenes (who knew the scenes weren’t shot in sequence?), the one where Don Q has fled to his hideout in the ruins of the DeVega ancestral castle, when a hinge on the secret trapdoor came loose.

“Jessie! Find a grip right away.”

I came across Zeke in the shade of a low-hanging eucalyptus at the edge of the back lot and pulled him from his lunch pail to the castle hideout. Crouching beside him, handing him his tools like a nurse in an operating room, I felt a prickly sensation on my neck. I’ve always been able to sense when I’m being watched—it comes from years on the stage where the ability to draw attention is essential to success.

“Who’s that?” I heard a deep voice whisper.

“The new Girl Friday, Jessie Beckett.”

I stood up and turned to face the great Douglas Fairbanks, Son of Zorro, not three steps away.

He looked every inch the Spanish don of the last century, costumed in tight pants and a white blousy shirt with a flowing silk tie and bolero jacket. He had played the hero in the 1920 feature Mark of Zorro—a completely new style of picture full of action and adventure—and now, five years later, he was back for the sequel as Zorro’s son, Don Q, wrongly accused of murdering the Archduke and desperate to woo the fair Dolores. I’d seen him on the set, of course, but this was the first time we had actually been introduced.

From a distance, Douglas Fairbanks was a tanned, muscular young man, but up close, the receding hairline and the wrinkles around his mouth and eyes betrayed him. I felt a stab of sympathy. I, too, had specialized in younger roles, playing a fourteen-year-old in vaudeville with the Little Darlings well into my twenty-fifth year, and I understood all too well the terrifying prospect of aging out of one’s livelihood. It had recently happened to me.

“How do you do, Mr. Fairbanks?” I said, looking steadily into his eyes, according him the respect he had earned without any of the toadying I knew he would loathe.

He gave me the casting director once-over, stepped closer, locked those piercing gray-blue eyes on mine, and put both hands firmly on my shoulders. Without a word, he walked me backwards until I bumped into a paper maché castle wall that looked more like the real thing than the real thing. Two dozen people on the set froze. With my shoulders pinned to the wall, I probably looked as thunderstruck as I felt.

“Chin up,” he commanded in a voice that was clear and strong and accustomed to obedience. “Hold still, now.” And yes, I did think, for one appalling moment, that he was going to kiss me, right there, in front of the entire cast and crew.

Snatching a clipboard from the hand of an assistant, he set it on my head and made a pencil mark on the fake stone wall.

“How tall is she?” he demanded of no one in particular. An alert gaffer whipped out a tape measure and held one end at my heel.

“Five one,” the man announced. “With shoes.”

“I thought so. Exactly the same as my Mary. But not as slim, I’ll wager. How much do you weigh?”

“Um . . . about a hundred pounds.”

“Mary weighs 95. And she struggles mightily to hold onto that number, I can tell you. Never touches sweets. Well, well, maybe we can use you as a stand-in some time, eh, Jessie Beckett? A blond wig to cover up that auburn bob and you’d be all set.”

A stand-in for the incomparable Mary Pickford, my idol and the most recognized face in the world? I swallowed hard but no words came out.

“All finished here.” At that moment, the grip climbed through the trapdoor, oblivious to the odd scene that had just played out above him. The cast and crew scurried to resume their places and pretend nothing out of the ordinary had occurred.

It was a week or so after that incident, at a break during the brutal swordfight scene between our hero, Don Q, and the dastardly Don Sebastian, that Mr. Fairbanks sent for me to come to his dressing room. The makeup artist was leaving just as I arrived.

“Ah, there you are,” said Mr. Fairbanks. “Come in, come in. Step lively, there isn’t much time.”

He must have sensed my nervousness because he lost no time in putting me at ease by telling me that Frank Richardson, the director, and Pauline Cox, the script girl who was training me, were pleased with the job I was doing. Then he asked how I liked working at Pickford-Fairbanks.

“I like it very much,” I replied uneasily, fearing this was to be my last day.

“Frank says you were in vaudeville. What brought you to Hollywood?”

“I spent my life in vaudeville, but I was ready for a change. Twenty-five years was enough.”

“Jesus, I thought you were about eighteen. How old are you?”

“Twenty-five. My mother was on stage while she was carrying me, so I tell people I started performing before I was born. Last fall, I took some civilian work and ended up with a broken leg and living with my grandmother in San Francisco while it mended. A vaudeville friend, Jack Benny, knew I’d had enough of the vagabond life and made inquiries for me. Zeppo Marx told Benny that Frank Richardson’s Script Girl was planning to get married, and I applied for the position before Frank even knew she was leaving.”

“If Zeppo vouched for you, I’m sure Frank counted himself lucky to get you.” He offered me a Camel, which I declined, and lit one of his own. “So you came to Hollywood to become a star, eh?”

“Doesn’t everyone want to become a star?” I asked, relaxing a little now that I realized I wasn’t going to be fired. “But I expect my years on the stage left me a little more realistic than most. I figure to learn all I can about the moving picture business—it’s a lot different than vaudeville—and then I’ll find out where I best fit in.”

“Well, Jessie Beckett, I’ll tell you where you best fit in. If you agree, that is. My personal assistant was called home to Texas yesterday to comfort her dying father. I need someone to fill her shoes for a while, and Frank offered you up. Pauline says it’s okay; she’s got six weeks before she leaves and that’s plenty of time to get you trained. It’s a temporary assignment, you understand,” he warned. “When my assistant comes back, she picks up where she left off, and you’re back with Frank. Are you interested?”

“Oh, yes, sir. Very much.” In the distance, a harsh bell sounded, signaling the end of the break. Douglas Fairbanks extinguished his cigarette, picked up a stack of papers, and continued talking as we walked out of his dressing room toward the sunlit stage.

“Good girl. Job starts now. Here, take these folders to Director Beaudine on the Little Annie Rooney set, call for the studio mail at the post office—something you’ll do twice a day—take it to the office and my secretary will show you how to sort it and what to answer. Stop by Kress’s and pick up a hat and some other things they’ll have waiting for you. Bring them here before three. Do you have all that straight?”

Other than the fact that I had no idea where those places were, sure. “Yes, sir.”

“‘Sir’ is for the stage, Jessie. ‘Douglas’ will do off it.”

By now we had reached the castle-ruins set. The great actor threw back his shoulders, straightened his doublet, narrowed his eyes to a steely glare, lifted his chin, and transformed Douglas Fairbanks into the fearless Don Q, son of Zorro. “Robledo!” he barked imperiously, one hand held out, palm up. “My sword!” Both cameras rolled.

Douglas Fairbanks was as good as his word. When his assistant returned after a few weeks, I went back to working as the film’s Assistant Script Girl. But during those weeks, I learned my way around Hollywood, met a slew of big shots and stars, and got invited to the party where the first of the “Hollywood murders” took place.

Chapter 2

“Are you very, very certain the invitation included me?” Myrna asked as we stepped off the electric streetcar—called Red Cars or Yellow Cars around here—on Saturday night and headed toward the home of one of Paramount’s leading directors.

“Of course it did,” I replied in a confident tone designed to conceal my own misgivings, but in truth, it had been rather an odd invitation, extended on impulse only yesterday when I delivered some papers to the office of the famous director, Bruno Heilmann. I had no written invitation to get us past a butler. What if no one expected us? Being turned away like gate-crashers in front of other guests would be humiliating.

“I was at Bruno Heilmann’s office on business three times this week, and yesterday I explained to him that it was my last day and that he could expect Mr. Fairbanks’s regular assistant to pick the papers up on Monday. He looked at me like he was trying to figure out a puzzle, and then he said”—and here I mimicked him here with my best German accent—“‘I’m hafing a party at my house tomorrow night. Everyone vill be there. Vill you come?’” So I said, ‘Sure, what time do you want me?’ and he said that most people would be arriving after nine. Then I asked, ‘What do you want me to do?’ He gave me the strangest look and said, ‘Vat do you usually do at parties?’ That was when I realized my mistake. ‘You mean, you want me to come as a guest?’ I said. ‘Of course,” he said. ‘Vat did you think I meant?’ And I had to admit: ‘I thought you were asking me to help out taking coats or passing caviar.’ He laughed so hard he had to wipe his eyes.”

Myrna was laughing too. “You didn’t!”

“I’m afraid I did. But the minute I understood it was an invitation and not a job, I thought how much I’d rather come with a friend. I figured since he was laughing, the odds were in my favor, so I asked. He said, ‘A girl friend or a boy friend?’ I said, ‘A girl friend who shares a house with me.’ ‘Is she pretty as you?’ he asked. ‘Prettier,’ I said.”

“Aw, come on!” she said, nudging me with her elbow.

Myrna was not a classic beauty like Gloria Swanson or Greta Garbo. Cataloged individually, her features were nothing unique—a cute upturned nose, wide set blue eyes, and high cheekbones—but the package sure turned heads. At nineteen, her carrot hair was maturing to a more sophisticated hue, her freckles were fading, and her soft, sexy voice was deepening . . . not that that would help her until someone figured out how to make pictures with sound. I had been in vaudeville dance acts for years and was a pretty good hoofer myself, but Myrna was a gifted, classically trained dancer who made reaching for the salt look like something out of Swan Lake. She had recently left her dancing job for a shot at the silver screen. With the predictable outcome . . . that is, none. We met two months ago when I took a room in the house on Fernwood Avenue where she lived with Melva, Helen, and Lillian—all nice girls, but I liked Myrna best.

The noisy commercialism of Hollywood Boulevard faded behind us, replaced with the sound of crickets and the exotic fragrance of eucalyptus trees as we wound our way through the narrow roads of Whitley Heights. Although there were no street lamps, a nearly full moon lit our stage like a distant floodlight. “The stars are out tonight,” I said.

“I hope I meet some. What if no one will talk to us?”

“Then we’ll talk to each other. But don’t worry. Douglas Fairbanks, at least, will talk to us. He told me he’d be there tonight for a short while, and he’s always so kind to his people. And we’re bound to know some of the others,” I said with more hope than certainty. “Surely someone from Son of Zorro will be there. And maybe from Ben Hur.”

“Even so, they won’t know me. I’m just an extra.” Myrna was still glum over her recent failures. She had tested for the Virgin Mary with Ben Hur but came away with only a $7.50-a-day job as a Roman senator’s mistress at the chariot races. Earlier she’d tested for a role with the great Rudolph Valentino in Cobra but missed that one as well. Too young for the part, Valentino had ruled.

We stepped through a gate and into a semicircular courtyard with five Spanish-style haciendas arranged in an arc around a dolphin fountain spouting streams of water. There was no mistaking the house—flaming torches lit the path to Bruno Heilmann’s front door.

“Good thing Mr. Heilmann put torches out or we’d never have guessed which place was his,” Myrna deadpanned.

I smiled. The Heilmann home could have doubled as an advertisement for the electric company, with light spilling out of every open door and window, raucous laughter surging and ebbing like waves at the seashore, and lively band music pulsating from behind the house, competing with the people indoors who were lustily singing to piano accompaniment. I’d been to parties in Hollywood but nothing highbrow like this.

“It looks like he invited all the neighbors,” I said, indicating the other four houses that were dark.

“That or they left town before the ruckus started!”

We approached the wide-open front door. Inside it was wall-to-wall actors, actresses, directors, and studio big shots, all dressed to the nines in dinner jackets and glamorous flapper dresses that bared more arms, shoulders, calves, and backs than you could see at a burlesque show. A thick haze of cigarette smoke clogged the air. Myrna and I exchanged nervous glances, put on our most confident smiles, and stepped into the foyer. When no one sprang from behind a corner to challenge us, my fears receded.

Bruno Heilmann didn’t live in one of those flashy mansions you see photographed in Motion Picture, Photoplay, or any of the fan magazines. We could see most of the first floor from the foyer, all of it decorated in the modern German style, cold, spare, and angular, with subtle colors, no bric-a-brac, and lots of abstract paintings. Intimidating, like its owner, but not overly large. I guessed he didn’t need a huge place, being a bachelor.

A butler descended the stairs to take our wraps. Several couples wobbled past him on their way to the second floor, planting each footstep with care and steadying themselves with the handrail.

I wore a custom-made, sleeveless tea-length frock, green to bring out the color in my eyes, with bugle beads sewn onto every square inch. It was expensive, left over from my last role where I had played the part of a long-lost heiress in a swindle to bilk her relatives out of her fortune. No one cared to have the clothes back, so I kept them. Myrna was dressed in her finest, a blue silk backless with handkerchief hem, not costly, but Myrna could wear rags and look like a million bucks. Still, she came across very young and inexperienced. I made a mental note to keep an eye on her.

“Shall I use your new name?” I asked, thinking ahead to the introductions.

She nodded uncertainly, then sighed. “I suppose so. I’ve just started using it on the back of my photographs and to sign my checks.”

“Good girl. It’s a great name.” The artistic, avant-garde crowd she hung around with had been urging her for some time to come up with a more distinctive sounding moniker, and she had finally settled on one.

“Every one of my friends thought Williams was too ordinary for an actress. I still consider it a very, very good name, but . . . well, I guess they were right. Anyway, everyone had ideas for my new last name—someone suggested Myrna Lisa, can you believe that?” She giggled. “It’s catchy all right, but I’d be too embarrassed to use something so silly.”

There must have been a hundred people at the party already, with more arriving behind us. We surveyed the living room from our vantage point at the top of the steps and jostled our way through the crush toward an enormous slate patio ringed with more torches. Colorful Japanese lanterns dangled overhead. In the space of sixty seconds I’d spotted several familiar faces from the Son of Zorro and a few people I’d met on my Fairbanks errands. I began to breathe easy. I could fit in here.

A waiter came near us with a tray of canapés, and I managed to snatch one. Another was taking orders for the bar. Myrna and I were about to request Gin Rickeys when I caught sight of a waitress circulating the room with a tray of champagne. My all-time favorite.

“Wait, Myrna! Have you ever had champagne?”

She shook her head.

“Try this,” I said, lifting two glasses off the tray and thanking the waitress with a smile.

She took a sip, but before I could hear her opinion, her eyes opened wide. “Gosh, there’s Raoul Walsh,” she said, pointing to the well-known director. I spun around. “He hired my dance troupe at Grauman’s Egyptian to do the orgy scene in The Wanderer. I was drinking and hanging over a couch with a wine goblet trying to do what they told me to do. It was really fun.”

“Can you introduce me?’

Her mouth turned down. “He doesn’t know me. I’m just a dancer.”

The champagne was delicious and cold as ice. It had not taken me long to realize that in Hollywood, as elsewhere, Prohibition laws were treated with the scorn they deserved. Liquor was served at every party, brazenly, defiantly, without fear of raids, arrests, or fines, not merely because the police were bribed as they were in most cities, but because the studio bosses ran the show here. The police did what they were told.

Every man in the room was handsome and every woman beautiful, so why I should find myself staring at one particularly compelling, dark-haired gentleman, I do not know. He had just entered the house and was standing in the foyer unaccompanied, surveying the crowded room. His eyes worked from right to left quickly, then back again more methodically, until he had taken stock of every face. It reminded me of another man I used to know—a bootlegger—who did the same thing before entering a room. All at once a shout came from behind me, and an actor I recognized from the screen as Jack Pickford called, “Johnnie! Over here!” Only then did Johnnie descend the two steps into the living room and plunge into the party.

Someone tapped my shoulder and there was Douglas Fairbanks in his smart midnight-blue dinner jacket, looking like he just stepped out of a high-society picture. “Good evening, Jessie,” he said, sipping a frosted glass of orange juice. “You’re looking lovely tonight.”

“Thank you. I’m here with a friend, and I’d like you to meet her. This is Myrna Loy.” And for form’s sake, I added the entirely unnecessary second half of the introduction, “Myrna, this is Douglas Fairbanks.”

Douglas made a short bow. “Charmed, I’m sure, Miss Loy.”

Myrna stood rooted to the rug, hopelessly tongue-tied. “Gee, Mr. Fairbanks. This is such an honor. I, um—I’ve seen all your pictures.”

“Until recently, Myrna was a dancer at Grauman’s Egyptian Theater,” I said helpfully, nudging her with my elbow.

“Um, that’s right, I used to dance the prologue to Thief of Bagdad.” She was referring to the lavish live spectacle presented on the stage before every showing of Douglas’s most recent film, a fairy tale with astonishing special effects that had been released last year and was still playing in many theaters.

“So you and I have shared the same stage, so to speak? Allow me to express my gratitude for your part in making my picture such a success. Ah, here she is . . . Mary, darling, I’ve told you about my temporary assistant. This is Jessie Beckett and her friend, Myrna Loy.”

As one of the few adults whose height matched that of “Little Mary” Pickford, I could look her straight in the eye. “I’m honored to meet you,” I began, trying not to appear over-awed by her presence and hoping she couldn’t see my heart hammering beneath my frock. I’d seen her at the studio a few times, but being introduced socially almost took away my powers of speech. “I’ve learned so much from you over the years, I feel I owe whatever success I had in vaudeville to you.”

“How very kind.” Mary Pickford looked even prettier than she did in her pictures, with wide hazel eyes and delicate lips darkened red. Her voice was higher than I had imagined and soft as a cat’s fur. For the party, she had swept her famous blond ringlets in a mass behind her head and donned a pale gold flapper dress embroidered with pearls. Hard to believe I was talking to the woman who had virtually invented film acting, the woman who had not only starred in hundreds of pictures, but who had started her own studio; the woman who could play a feisty eleven-year-old boy as convincingly as she did an old woman. I’d’ve rather met “Little Mary” than the Queen of England.

“Douglas said you played children’s roles in vaudeville?” she asked politely, sipping her orange juice and no doubt wondering why a lowly assistant script girl had been invited to this chic affair.

I nodded. “I grew up on stage too. Just like you. My mother was a headliner, and she managed to keep both of us working most of the time.” The truth was, things were pretty darn good while Mother was alive. It was later, after she died, that my life fell apart.

“No father?”

“Died.”

Sympathy wrinkled her smooth brow. “Oh, Jessie, so did mine. And my mother took us kids—Lottie and Jack and me—on the stage and managed our careers. She still does. I don’t know what I’d do without her. I’ll bet you never went to school either.”

“You can’t go to school when you move to a different city every week. My mother taught me my letters and numbers, and I read every book I could lay my hands on.”

“I learned to read from the billboards along the train tracks,” Miss Pickford said, shaking her head with the wonder of it. I was about to ask her what early roles she had played, when she said, “What sort of roles did you play?”

“My first was Moses in the bulrushes, the second was Baby Jesus. After that I specialized in kidnapped baby roles, caterwauling like the devil during chase scenes. When I got old enough to memorize lines, I played the brat in Ransom of Red Chief and scenes from Romeo and Juliet, that sort of thing.”

She gave a knowing nod and smiled at the recollection. “I played Juliet myself. I milked that death scene for all it was worth!”

“Juliet was my first death scene . . . they became something of a specialty for me: Juliet, Ophelia, Desdemona, Cleopatra—”

Miss Pickford’s perfectly arched brows moved together in a slight frown. “Ophelia doesn’t have a death scene.”

I waved my hand dismissively. “Yes, I know. Shakespeare missed a real opportunity there, so we added one. Audiences love death scenes and mine were pretty darn convincing. As I got older, I continued with the kiddie roles. It was what I knew best and my size let me get away with it. I learned the tricks of the trade from watching your pictures.”

Miss Pickford smiled, putting her hand lightly on my arm, almost as if we were real friends. “And what tricks were those?”

“Well, for one, to keep thin and flat-chested. And to make short, quick movements. Also, to add a skip to my step whenever possible. To accentuate my freckles and keep my fingernails short and unpolished. And of course, to keep my hair in long ringlets.”

“But you’ve bobbed yours.” She sounded envious.

“Just a couple months ago. I hated those curls!”

“I loathe mine. So babyish! Now don’t you dare tell a soul I said that! Not a day goes by that I don’t wish I could cut my hair, but my public would think it a betrayal as bad as Benedict Arnold’s and would probably quit watching my pictures. I don’t dare risk it.”

I was a more than a little surprised at this confession. Like most people, I had supposed that “The Most Popular Girl in America” did whatever she wanted. Suddenly I saw how naive that was. In some respects, Mary Pickford was a prisoner of her image.

For a few minutes, we swapped recollections of night trains, dollar hotels, and boarding house food, until a waitress carrying a tray of champagne approached. I set my empty glass on the tray and picked up a full one. Miss Pickford glanced over her shoulder, then did the same, replacing her glass of orange juice with one of champagne.

“Don’t tell Douglas,” she said with an exaggerated wink. “He disapproves of alcohol. Usually I try to accommodate him, but, well, sometimes I get tired of pleasing everyone else.”

At that moment, her attention was drawn to someone behind me. I turned to see her younger sister, Lottie Pickford, making her way unsteadily toward us. Lottie wore a wild look as she clutched at Mary’s arm.

“Lottie, what on earth—?”

“Can you—have you—?” Her eyes darted around the room, frantically searching right and left.

“Lottie, darling, I’d like you to meet . . .” But Lottie must have spotted the person she was looking for, because she stumbled toward the stairs without uttering another syllable. A few steps away, Douglas took in the entire scene. His well-disciplined actor’s features failed him for a moment and his eyes narrowed to dark slits. His lips tightened. With a jolt of surprise, I read disgust on his face. Clearly, Douglas despised his sister-in-law.

“I’m sorry . . .” Miss Pickford began, but I waved off her apology.

“I already know Lottie from Son of Zorro.” Lottie had a small but significant role in the picture as Lola, the pretty servant girl who serves as a spy in Don Fabrique’s employ and uncovers the blackmail plot. Lottie was usually late to work and often petulant, but no one dared reprimand the sister-in-law of Douglas Fairbanks. Only now did I realize his courteous treatment of her on the set masked his true feelings. And as I watched Lottie’s behavior, I understood the reason for his contempt. Douglas Fairbanks despised liquor, and Lottie was a drunkard.

“Oh, of course you do. I forgot, you work for Frank Richardson now. Well, excuse Lottie’s bad manners tonight, I’m afraid she’s dealing with some—”

Whatever she was going to say was interrupted by a shrill scream and the sound of pottery breaking into a hundred pieces, followed by furious accusations from the other end of the room. Too short to see and too curious for my own good, I stepped up on one of the chairs that had been pushed against the wall.

Two women in sparkling gowns were hurling insults until one of them, the older one, lost all sense of decency and pulled back her bejeweled hand. With a lightening movement, she smacked the younger woman across the face, pushed through the throng toward the door, and stormed into the night. The victim staggered but did not fall, thanks to the quick reaction of a couple of men nearby who held her close. The stunned silence quickly filled with a babble of conversation as the guests analyzed the spat.

“Seems like a disagreement,” I said lamely, stepping down off the chair. “I wonder who that was.”

Miss Pickford sipped her champagne calmly. “That was Faye Gordon who just left.” I looked surprised, as little Mary Pickford could not have seen over the heads to the other side of the room. She read the question in my eyes and gave a rueful smile. “I recognized her voice, and throwing breakables has become something of a trademark with Faye. Poor dear, she has had some bad luck lately, but she should learn to keep her temper in check, at least in public. And this,” she said grandly as an attractive couple approached us, “this handsome man is my darling brother Jack and his wife, Marilyn Miller.”

Compared to their famous sister, Jack and Lottie Pickford were amateurs, but they were good-looking and competent enough on screen. Marilyn Miller and I were almost the same age, and I knew her from vaudeville. When she didn’t seem to recognize me, I tried to spark her memory by saying, “It’s so good to see you again, Marilyn. You may not remember, but we knew one another some years ago in vaudeville when we were children. You were touring with your family as the Five Columbians and my mother and I had a mother-daughter act.”

She didn’t respond. A little embarrassed, I tried again, “Remember how we were always dodging the sticklers who were trying to enforce the child labor laws?”

Then I looked at her more closely and noticed the empty eyes—her pupils were deep black pools so large I couldn’t tell what color her irises were—and I guessed why so many party guests were going upstairs. Bruno Heilmann might flaunt the Prohibition laws downstairs, but even he couldn’t be so cavalier about narcotics. I looked back at Jack Pickford. His pupils were enormous as well. Cocaine or hashish, probably, although I’d seen enough heroin and morphine since I’d come to Hollywood to know those were popular party fare too.

Marilyn and Jack did not incline toward conversation, at least not with me. Jack made a curt remark to his sister, then pulled his wife to the front hall where he erupted into a tirade, berating the stone-faced butler who had brought down the wrong wraps.

Miss Pickford didn’t appear to notice. She reached toward Douglas who was still chatting with Myrna and two other fawning women. “Duber, let’s go or we’ll be late to the Gishes.” She turned back to me. “Douglas was right when he said I would enjoy meeting you, Jessie. I’m sure we’ll see you around town in the near future, and we can talk again about vaudeville. Excuse us, please, we have another stop tonight before we can go home and relax.”

The crowd did a Red Sea parting as the Hollywood royalty made for the exit. The champagne waitress passed again, this time giving me a long, measured look that I found disconcerting. Myrna lifted two glasses off her tray. “Here, let’s toast! To the most exciting night of my life!” She bubbled more than the champagne. “Imagine—little Myrna Williams—I mean, Loy—talking to Douglas Fairbanks for ten whole minutes! No one would believe it back home in Montana. And did you get to meet Jack Pickford? Isn’t he a dream?”

“Actually, we were introduced, but he wasn’t in a sociable mood.”

“Do you know the scandal about his first wife’s death? You must remember! It was all over the newspapers about five years ago. Olive Thomas was her name. She was a real vamp, very, very gorgeous and a big star.”

Who hadn’t heard the tale? Actually knowing some of the people involved brought the story closer to home. I remembered Olive Thomas from her pictures and from her mysterious death in Paris.

Myrna continued. “I was only fourteen at the time, but I read all about it in the magazines. I never believed Jack’s claim for a minute. You tell me, please, how anyone could accidentally drink an entire quart of nasty-tasting toilet cleaning solution at three A.M. without noticing something tasted funny. Did you think it was suicide or murder?”

“I never could decide. The reports I read said it wasn’t toilet cleaner, that Jack had lied so the press wouldn’t learn the truth and ruin his career.”

“What was it?”

“Bichloride of mercury. You know what that’s for, don’t you?” I had understood the sexual implications at the time, but Myrna was younger and probably never caught on. “Syphilis,” I told her. “I kind of thought that maybe her death really was accidental, that both of them were so high on cocaine and booze that they didn’t know what they were doing.”

“I overheard my mother and her friends talking about it. One of the neighbors insisted that it was suicide, that Olive was depressed over their awful marriage. Another thought Jack murdered her. My mother still thinks that she was planning to poison Jack, but drank it herself instead by mistake, but that sounds impossible. I guess no one will ever know the truth.”

“The French police certainly didn’t bother to find out. They couldn’t send the body home fast enough. The sad thing was that all those tales of wild living spilled over to Mary Pickford, dragging her name through the mud along with Jack’s, even though she wasn’t within a thousand miles of Paris and had nothing to do with any of it.”

“Gosh,” said Myrna, “that’s not fair. Anyway, I’m surprised to see Jack and Marilyn together tonight. This month’s Photoplay says they are getting a divorce, but they looked happy enough tonight.”

“Myrna, those magazines are full of lies. You can’t believe a word they print. All these big actors have press agents who’ll say anything to get publicity. They make up ninety percent of it. Here, I’ll prove it. You know how everyone says Douglas Fairbanks does all his own stunts? Well, he does most of them, true, but I’ve seen a stunt man do a few.”

“Really?”

“Excuse me, don’t I know you?” A woman wearing a short, chic gown came up to Myrna and me. “Weren’t you at Pickfair last Christmas?”

Before I could respond, two young men cruised over. “Haven’t we met before?” asked the one with the dimples. “Of course we have,” said his friend, answering for me, “at the Montmartre that night Rudy was doing the tango, wasn’t it?”

The cynic in me knew exactly what had prompted the sudden spike in our popularity—people had seen Douglas Fairbanks and the Pickfords talking to us and assumed we were “somebody.” Somebody they couldn’t quite place . . . Thus elevated to the ranks of the Hollywood elite for a few short hours, Myrna and I basked in our new status like two Cinderellas before the final stroke of midnight returned us to reality.

Murder Off Stage

Murder Off Stage

like me on Facebook follow me on twitter linkedin pinterest rss